|

Sublime Numbers |

|

|

|

For any positive integer n let τ(n) denote the number of divisors of n, and let σ(n) denote the sum of those divisors. The ancient Greeks classified each natural number n as "deficient", "abundant", or "perfect" according to whether σ(n) was less than, greater than, or equal to 2n. Notice that the number 12 has 6 divisors, and the sum of those divisors is 28. Both 6 and 28 are perfect numbers. Let's refer to a natural number n as "sublime" if the sum and number of its divisors are both perfect. Do there exist any sublime numbers other than 12? |

|

|

|

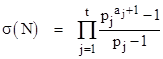

To answer this question, recall that for any integer N with prime factorization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

we have |

|

|

|

|

|

Also, every even perfect number is of the form (2s – 1) 2s–1 where 2s – 1 is a prime. Thus an even perfect number has exactly one odd prime factor. |

|

|

|

Now suppose N is divisible by exactly k powers of 2. It follows that σ(N) is divisible by 2k+1 – 1, which is odd, so this must be a prime (else it would factor into two odd primes). Also, all the other factors of N must then contribute a combined factor of 2k to σ(N). But each odd prime power pd contributes a factor of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

to σ(N), which can only be even if d is odd, in which case it factors as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The right hand factor can be even only if t is odd, in which case it factors as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

However, the factors (1 + p) and (1 + p2) cannot both be pure powers of 2, because if p = 2r – 1 then 1 + p2 = (2)(2[2r–1] – 2r + 1). Therefore, if the number σ(2kG) is perfect, then G must be the product of distinct Mersenne primes pj = 2aj – 1 where the exponents aj sum to k, where k + 1 is also a "Mersenne exponent". |

|

|

|

Moreover, to make τ(N) perfect, it's necessary for k+1 itself to be a Mersenne prime. Thus, to construct an example of this type, we need to find a Mersenne exponent E that is also a Mersenne prime, and such that E–1 is expressible as the sum of exactly log2(E+1)–1 distinct Mersenne primes. |

|

|

|

One example is E = 3, because 2 can be expressed as the sum of exactly log2(4)–1 = 1 Mersenne primes, i.e., 2 = 2. Thus, we have N = (23-1)(22–1) = 12. Other possible values of E are 7, 31, 127,..? It isn't possible to express 6 as a sum of two Mersenne primes, nor 30 as a sum of four distinct Mersenne primes. However, 126 can be expressed as a sum of six distinct Mersenne primes as follows: 61 + 31 + 19 + 7 + 5 + 3. Therefore we have |

|

|

|

N = (2126)(261–1)(231–1)(219–1)(27–1)(25–1)(23–1) |

|

|

|

Thus if we set N equal to |

|

|

|

6086555670238378989670371734243169622657830773351885970528324860512791691264 |

|

|

|

we find that σ(N) and τ(N) are both perfect, so this is the second sublime number. In summary, both of the known sublime numbers are based on a Mersenne prime of the form q = 2k – 1 where k = 2j – 1 is also a Mersenne prime and k – 1 is the sum of exactly j – 1 distinct Mersenne exponents. The only known primes q = 2k – 1 with k = 2j – 1 are given by k = 3, 7, 31, and 127. However, (7 – 1) is not a sum of two Mersenne exponents, nor is (31 – 1) a sum of 4 Mersenne exponents. Thus, the only two known sublime numbers are based on the sums |

|

|

|

(3 – 1) = 2 |

|

|

|

Assuming there are no odd perfect numbers, there can be no more even sublime numbers unless there are other (presently unknown) Mersenne prime exponents that are themselves Mersenne primes. Given that the exponents 131071 and 524287 have already be checked, the next possible exponent would be 231 – 1, which is 2,147,483,647. Even with the Lucas-Lehmer test I think this exponent would be a challenge. Notice that we would not only need to test this particular exponent, but all exponents less than this one, in order to decide if this number minus 1 was expressible as a sum of distinct Mersenne exponents. The next possible exponent would be 261 – 1, which is certainly far out of reach for any known method of testing. |

|

|

|

It remains to consider the possibility of an odd sublime number (again assuming no odd perfect numbers). By the same arguments presented above for even sublime numbers, we know that an odd sublime number must be of the form |

|

|

|

N = qr (p1 p2 ... pt) |

|

|

|

where r = 2j – 2 is one less than a Mersenne prime, t = j – 1, and the pi = 2ki – 1 are distinct odd Mersenne primes and q is an odd prime. Also, we must have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where (k0 – 1) = k1 + k2 +... + kt . To give a "non-example", consider the case of q = 5, j = 2. This gives r = 2, so the above expression is (53 – 1)/(5 – 1) = 31, which is a prime of the form 2k0 – 1 with k0 = 5. Therefore, we need only express (5 – 1) = 4 as a sum of (j – 1) distinct Mersenne exponents. Since j – 1 equals 1 in this case, it requires that 4 itself be a Mersenne exponent, i.e., we need 24 – 1 = 15 to be a prime, which of course it isn't. If it was, the number N = (52)(15) = 375 would have τ(N) = 6 and σ(N) = 496, and so 375 would be an odd sublime number. |

|

|

|

The above shows that the first step to find an odd sublime number is to find an odd prime q and two Mersenne primes m1 = 2j – 1 and m2 = 2k – 1 such that (qm1 – 1) = (q – 1) m2. If we can find such primes, then we need to express k – 1 as a sum of exactly j – 1 distinct Mersenne exponents. Is there a simple way of proving this is impossible? |

|

|