|

Terza Rima |

|

|

|

Everyone here is wearing a uniform… don’t kid yourself. |

|

Frank Zappa |

|

|

|

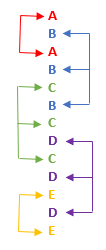

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) made use of an interesting rhyming pattern, called terza rima, in his epic poem, The Divine Comedy. Terza rima literally means “third rhyme”, and it consists of an interlocking sequence of triple rhymes, as shown below: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A poem in terza rima usually begins with a double rhyme A-A as shown here, followed by the interlocking sequence of triple rhymes, and finally concluding with another double rhyme at the end (E-E in this short illustration). There are many variations, though, such as omitting the final E-E lines and ending the poem with a DD couplet. Dante apparently invented this rhyming pattern for The Divine Comedy, and it may have contributed to the success of that work, which was designed to be a “page turner”. Each canto ends with some kind of cliff-hanger or tease that encourages the reader to go on to the next section. The interlocking rhyme scheme has a similar effect, in miniature, since there is always a pending rhyme to be resolved. (It’s slightly reminiscent of the interlocking sequence of chemical bonds in the double helix of DNA molecules.) |

|

|

|

Arguably, it’s easier to make use of terza rima in the Italian language, partly because Italian is a highly gendered language, such that many words end with one of just a small number of vowel sounds (bambina, bambino). In contrast, most English words (e.g., infant) are ungendered, and end with consonants with a wide variety of sounds, so English isn’t as “rhyme-rich” as Italian. Nevertheless, there are many examples of the use of terza rima in English poetry, such as Chaucer’s “Complaints to His Lady”, Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”, and Frost’s “Acquainted with the Night”. Dante used 11 syllables per line (hendecasyllabic), but iambic pentameter (10 syllables per line) seems to be more natural in English. |

|

|

|

To illustrate with a contemporary example, the poem below, “Play by Play” by David Abierre, is written in fairly strict terza rima. The meter might be called fractured iambic pentameter, because although it has 10 syllables per line, it doesn’t respect the classical stress patterns of iambic pentameter. As a result, the main rhymes are somewhat muted, if not inaudible. Interestingly, when spoken, some non-rhymes (such as ours / avatars) tend to stand out as if they were rhymes, just because they are near rhymes and the meter happens to accidentally align. |

|

|

|

Play by Play |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the midst of my life, straying through pale |

|

woods, a kaleidoscopic glimmering |

|

diverts me wayward down a tangled trail… |

|

but wait, let me start at the beginning. |

|

So, there’s this woman, let’s call her Jane Doe, |

|

who plays Lacey, an internet darling. |

|

Now, Lacey’s an actress too, in whose show |

|

others are portrayed in a vivid blur |

|

of passion, jealousy, comfort, and woe: |

|

There’s the pining ex, possessive lover, |

|

friend’s sister, sister’s friend, bratty princess, |

|

vampire, a yandere kidnapper, |

|

Mafia boss’s daughter, maid, waitress, |

|

a professor and chanteuse, a bully |

|

cheerleader, a scheming boss, and, who’d guess, |

|

every one of them is in love with me. |

|

But, of course, I’ll not be flattered or drawn |

|

in, not charmed by this faux felicity. |

|

I’m seeking Jane Doe. Jane Doe. Is she pawn |

|

or queen, player or played? I’d comprehend |

|

this occulted dame and the path she’s on. |

|

I picture Jane hunch-backed, one leg shortened, |

|

disfigured visage, rotund, and perforce |

|

abiding in shade… but her voice suspends |

|

this grief, a wondrous instrument that pours |

|

out sweet angels’ incantations, songs, prayer, |

|

salving whispers. With this dulcet chorus, |

|

abetted by the shapes and golden hair |

|

of Lacey, every mortal she endears. |

|

But just then it occurs to me: Is there |

|

a secretive cabal of puppeteers |

|

at work here? Producers, script consultants, |

|

graphic art designers, sound engineers… |

|

By this account, Jane herself is a front, |

|

an exquisitely crafted guileless |

|

waif, but who’s behind it, and what they want, |

|

I won’t speculate. And yet, I confess, |

|

some tender grace notes have disarmed me. Oh, |

|

if this be an artificial kindness |

|

generated in some covert bureau |

|

by algorithms designed to entice, |

|

I will not be ashamed to have been slow |

|

to admit it. No, Lacey will suffice, |

|

created and creating, branch and root. |

|

Take her at face value, an artifice |

|

or not. Upholding ours, we must refute |

|

the denigration of all avatars. |

|

With that thought I resign from this pursuit, |

|

and level up to see once more the stars. |

|

|

|

The title “Play by Play” may literally refer to the advancing sequence of little “plays” produced by Lacey, and to the common expression for a detailed account of events, but it also evokes the concept of a “play within a play”, since the person ostensibly enacting the characters is herself a character being enacted by someone else. These three layers are mirrored by the terza rima structure, which is also reminiscent of Hirschfeld’s famous poster for “My Fair Lady”, with the three layers of puppets and puppeteers. |

|

|

|

The use of established structural forms in poetry originated in ancient times, when everything was passed down by oral tradition, and the structure aided the memorization of book-length sagas. Similarly, Shakespeare’s use of iambic pentameter may have helped the actors memorize their lines… and yet, in mostly blank verse, Shakespeare created some of the most beautiful (not just memorable) verbal expressions in the English language. His use of rhyme in the plays was sparing, although his sonnets were all fit to a conventional rhyme scheme. |

|

|

|

One argument against rhyme in poetry (aside from potentially being distracting and aesthetically unpleasant) is that it’s an artificial constraint that may lead to compromises in the wording and what the poem is actually trying to convey. It’s been said that modern poetry shuns rhyme because it’s too easy to do badly and too difficult to do well. The demands of rhyme can certainly lead to the unnatural use of obscure words, witness Shelley’s “I silently laugh at my own cenotaph”, that is easily mocked, although he nearly redeems himself with “I arise and unbuild it again”. |

|

|

|

However, some kinds of lyrical poetry use voiced words purely for their sounds (the sonic aspect), as if the voice was a musical instrument, and rhyme is one of many possible audio effects. The music of Bach, for example, illustrates the greatness that can be achieved within formal structures. On the other hand, most modern poetry is based on the use of words for their meanings (the semantic aspect), not just their sounds. Ideally, a poem would use words in a way that both has the desired sound and conveys the desired meaning, but this may involve some compromises, especially for an objectively rigid structure imposed on the sounds, i.e., the meter and perhaps other sound effects such as rhyme. Frost once said he tried to make his poems have the sound of adults talking seriously in another room, when you can’t quite make out what they are saying. But, of course, he also made superb use of rhyme. |

|

|

|

Does rhyme ever add value to a poem? For example, does it add anything to Prince Hal’s announcement (in Henry IV) that “I’ll so offend to make offense a skill… redeeming time when men think least I will”? In the plays, Shakespeare used rhyme on an ad hoc basis, not with any obligatory structure. Rather than advancing the poem, a rigid rhyme structure can sometimes seem to be just fulfilling an arbitrary convention having nothing in particular to do with the content of the poem. Even when we can make an abstract connection between, say, the three coordinated levels of Jane / Lacey / Yandere and the triple rhymes of terza rima, this connection doesn’t necessarily enhance the visceral quality of the poem. It’s just an abstract congruence between qualitatively different things. Given the fractured meter, readers may not even be aware of the rhymes, and if they are, this doesn’t necessarily further their grasp of the three levels of volition in the story. |

|

|

|

On the other hand, a poem can certainly contain elements that aren’t immediately perceived on casual reading. For example, in the poem above, readers may or may not be aware that the first and last lines are paraphrases of the first and last lines of Dante’s Inferno, or that the poem is written with the same triple rhyme scheme as was used in Inferno. And if readers are aware, does it make a difference? What would they be expected to do with this abstract information? Are we to infer that this poem is some kind of miniature version of Inferno, or that it shares a common theme or plot with that other poem? Is the narrator’s journey through the world of Lacey being likened to Dante’s journey through Hell? (As an aside, were the three ghost/guides of Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” inspired by the ghost/guide Virgil in Inferno?) |

|

|

|

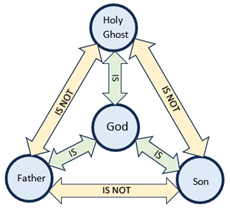

Numerology has often played a role in certain kinds of poetry (not to mention other art forms). For example, the triple-rhyme scheme used in Divine Comedy is often said to be associated with the Trinity in Christian theology, i.e., Father / Son / Holy Ghost. Whether this kind of abstract correspondence has any artistic value is questionable, although it does raise the interesting concept of non-transitive identifications (A=B, A=C, but B≠C). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But there are endless abstract patterns and numerological features that could likewise be mentioned. For example, the poem consists of 72 = 49 lines, and could have been broken into seven stanzas of seven lines each, possibly suggesting a correspondence with Dante’s seven levels of purgatory. But what purpose would be served by this kind of numerology (unless the narrative content actually broke down into those segments)? Are we dealing here with a poem to be perceived and appreciated, or a puzzle to be analyzed and solved? |

|

|

|

Admittedly, some poems are designed to be puzzles. In the example above, the narrator is not just perceiving Lacey’s presentation and appreciating it on its own terms, he’s trying to solve it, to comprehend the hidden (occulted) source, Jane Doe, or whoever stands behind her. He’s treating Lacey like a puzzle, an artifice. From this standpoint, it makes some sense that the poem itself would contain artificial and even cryptic elements and clues. Even if a reader doesn’t happen to recognize the connections with Inferno, it can still be perceived that the beginning and ending lines seem to “come from somewhere else”, and the rhyme pattern isn’t just random. The fractured meter tends to obscure the rhyme structure upon reading, and only becomes apparent by a meta-examination of the poem on paper, but this kind of abstract feature, isn’t necessarily illegitimate, since a work of art can be apprehended in different ways. |

|

|

|

One interesting aspect of the poem is its use of lists. First is the short list of “passion, jealousy, comfort, and woe”, followed immediately by the long list of exotic characters, spanning almost six full lines, from the “pining ex” to the “scheming boss”. Later we have the lists of negative and positive characteristics posited for Jane, and then the list of hypothesized puppeteers. There’s a long literary tradition of lists, such as the biblical lists of post-flood nations, the Israel census, Christ’s genealogies in Mathew and Luke, and so on. What is the reader (or listener) supposed to make of such lists? Are we supposed to recognize the names? What purpose do the lists serve? Shakespeare also sometimes made use of lists, as in |

|

|

|

the whips and scorns of time, |

|

the oppressor’s wrong |

|

the proud man’s contumely |

|

the pangs of dispriz’d love |

|

the law’s delay |

|

the insolence of office, and |

|

the spurns that patient merit of the unworthy takes. |

|

|

|

When someone remarked that Shakespeare had such a facility for verbal expression that he never blotted out a line, Ben Johnson supposedly said “Would that he had blotted out a thousand”, suggesting that he thought Shakespeare was a bit verbose at times (reminiscent of the famous admonition of Emperor Joseph II to his court composer: “Too many notes, Mozart!”). Granted, the items in Hamlet’s list are each interesting, and we wouldn’t want to omit them, but they arguably don’t advance the play other than to paint the picture of Hamlet’s intellectual character, illustrating how, even pondering this supposed extremity, he’s distracted and sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought. |

|

|

|

The long list of exotic characters in “Play by Play” includes mostly recognizable entities, although the effect may be somewhat superficial without knowing the back stories. They certainly don’t carry the intrinsic interest of a pithy list of life’s calamities. On the other hand, the very length and density of the list fulfills the promise of the kaleidoscopic glimmering, and may also be intended to have a comical effect, especially setting up the line “and every one of them is in love with me”. Making adjustments in terza rima is not trivial, like gene splicing, since the interlocking pattern needs to be maintained, but suppose the list had been abridged to something like |

|

|

|

There’s the pining ex, possessive lover, |

|

a professor and chanteuse, a pretty |

|

maid... a whole cavalcade, and I gather |

|

every one of them is in love with me! |

|

|

|

Would the effect of the poem have been enhanced or diminished by omitting most of the colorful list of characters? As a bespoke poem for a select audience familiar with the characters, the list may be justifiable, but for a general audience some abridgement might be preferable. |

|

|

|

Clearly, the poem isn’t just (or even primarily) about Jane/Lacey, it’s about the narrator. At its conclusion, the narrator seems to settle (provisionally?) on the idea that we all create our “avatars”, the personas to which we aspire, to represent ourselves, and that we should respect each other’s created identities. He decides to let Lacey be Lacey, and abandon his search for Jane. |

|

|

|

There’s an interesting dichotomy in poetry today. The only poetry consumed by most people is song lyrics, which make heavy use of repetitive meter and rhyme or near-rhyme. For example, one of the most perfect song lyrics, Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice”, contains a series of primitive triple-rhymes (although not terza rima), or what might be called dominant vowel-rhymes, such as road/told/soul. Similarly “Blowin In the Wind”, “I Want You”, and others are constructed with triple rhymes – not to mention the quadruple rhymes of “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and “Like a Rolling Stone”. In contrast, modern literary poetry eschews such mannered musical elements, and consists mainly of stridently un-structured forms. Still, modern poetry is itself a recognizable form, in the sense that people know what a “good” modern poem looks and sounds like, and things that don’t conform to that non-conformist template are excluded from the genre. |

|

|

|

Much of modern literary poetry is wonderful, and admittedly some of the old formalized Romantic poets are almost unreadable, but self-confident guardians of the modern aesthetic remind me of the 1969 Frank Zappa concert, when a rowdy crowd of hippies, beatniks, folkies, bikers, and college students were disdainful of the police working security, and shouted that everyone wearing a uniform should get out. |

|

|