|

6.1

An Exact Solution

|

|

|

|

Einstein had

been so preoccupied with other studies that he had not realized such

confirmation of his early theories had become an everyday affair in the

physical laboratory. He grinned like a small boy, and kept saying over and over

“Ist das wirklich so?”

|

|

A. E. Condon

|

|

|

|

The

special theory of relativity posits the existence of a unique class of global

coordinate systems - called inertial coordinates - with respect to which

inertia is homogeneous and isotropic. It was natural, then, to express

physical laws in terms of this preferred class of coordinate systems. The

special theory also strongly suggested the fundamental equivalence of mass

and energy, according to which light – and every other form of energy – must

be regarded as possessing inertia. It follows that the speed of light in

vacuum has an invariant value, c, in all directions in terms of any inertial

coordinate system. However, it soon became clear that the existence of global

inertial coordinate systems (with invariant light speed) together with the

idea that energy has inertia (as expressed in the famous relation E2

= m2 + |p|2) were incompatible with one of the most

firmly established empirical results of physics, namely, the exact

proportionality of inertial and gravitational mass. The latter implies that a

pulse of light must be deflected in a gravitational field, which clearly

requires the wavefront to have different speeds at different locations in

terms of suitable global coordinates. This incompatibility led Einstein, as

early as 1907, to the belief that the premise of global inertial coordinate

systems could not be maintained. We can establish inertial coordinates over

any sufficiently small region of space and time, but there do not exist any

global systems of inertial coordinates in regions where gravitating

mass-energy is present.

|

|

|

|

Since

no preferred class of global coordinate systems exists, the general theory

essentially places all (smoothly related) systems of coordinates on an equal

footing, and expresses physical laws in a way that is applicable to any of

these systems. As a result, the laws of physics will hold good even with

respect to coordinate systems in which the speed of light takes on values

other than c. For example, the laws of general relativity are applicable to a

system of coordinates that is fixed rigidly to the rotating Earth. According

to these coordinates the distant galaxies are "circumnavigating"

nearly the entire universe in just 24 hours, so their speed is obviously far

greater than the constant c. The huge implied velocities of the celestial

spheres was always problematical for the ancient conception of an immovable

Earth, but it is beautifully accommodated within general relativity, in which

any “fictitious forces” that arise in accelerating coordinates affect the

values of the metric components guv for those coordinates. When

expressed in a rotating system of coordinates, the distant stars are indeed

moving with dx/dt values that far exceed the usual numerical value of c, but

they are not moving faster than light, because the speed of light at those

locations, expressed in terms of those coordinates, is correspondingly

greater.

|

|

|

|

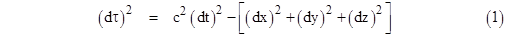

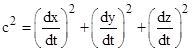

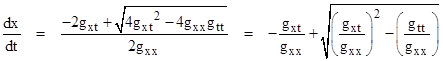

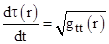

In

general, for any given system of coordinates the velocity of light can always

be inferred from the components of the metric tensor, and typically looks

something like  . To understand

this, recall that in special relativity we have global inertial coordinate

systems such that the metric tensor has the constant form . To understand

this, recall that in special relativity we have global inertial coordinate

systems such that the metric tensor has the constant form

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

trajectory of a light ray follows a null path, i.e., a path with dτ = 0,

so dividing by (dt)2 we see that the path of light everywhere

satisfies the equation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hence

the velocity of light is unambiguous in terms of these preferred systems of

coordinates. However, in the general theory we are no longer guaranteed the

existence of a global coordinate system with a constant metric of the simple

form (1). It is true that over a sufficiently small spatial and temporal

region surrounding any given event in spacetime there exists a coordinate

system of that simple Minkowskian form, but in the presence of a

non-vanishing gravitational field ("curvature") equation (1)

applies only with respect to "free-falling" inertial coordinates,

which are necessarily transient and don't extend globally.

|

|

|

|

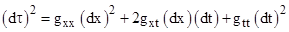

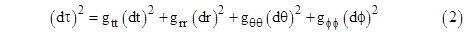

So,

for an extended region of spacetime, instead of writing the metric in the xt

plane as (dτ)2 = (dt)2 – (dx)2 , we

must consider the more general form

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

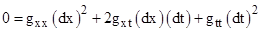

where

the coefficients are functions of the coordinates. As always, the path of a

light ray is null, so dτ = 0 and the differentials dx and dt satisfy the

equation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Solving

this gives

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If

we diagonalize our metric we get gxt = 0, in which case the

"velocity" of a null path in the xt plane with respect to this

coordinate system is simply dx/dt =  . This quantity

can (and does) take on any value, depending on our choice of coordinate

systems. . This quantity

can (and does) take on any value, depending on our choice of coordinate

systems.

|

|

|

|

Around

1911 Einstein proposed to incorporate gravitation into a modified version of

special relativity by allowing the speed of light to vary as a scalar from

place to place in Euclidean space as a function of the gravitational

potential. This "scalar c field" is remarkably similar to a simple

refractive medium, in which the speed of light varies as a function of the

density. Fermat's principle of least time can then be applied to define the

paths of light rays as geodesics in the spacetime manifold (as discussed in

Section 8.4). Specifically, Einstein wrote in 1911 that the speed of light at

a place with the gravitational potential φ would be c0 (1 + φ/c02),

where c0 is the nominal speed of light in the absence of gravity.

In geometrical units we define c0 = 1, so Einstein's 1911 formula

can be written simply as c = 1 + φ. However, this formula for the speed

of light – indeed, this whole approach to gravity – turned out to be

incorrect. In the general theory of relativity, completed in 1915, the speed

of light in a gravitational field cannot generally be represented by a simple

scalar field of c values in Euclidean space, due to the intrinsic

curvature of spacetime. In terms of some quite natural coordinate systems,

the speed of light varies not only from place to place, but also in different

directions at any given place (even though the speed of light always has the

invariant value c in terms of local free-falling inertial coordinates, consistent

with the equivalence principle). For example, near a spherically symmetrical

and non- rotating mass, we can define stationary coordinates in which the

speed of light is isotropic, but in these coordinates the circumference of a

circular orbit of radius r is not equal to 2πr. On the other hand, we

can define stationary coordinates in which a circular orbit of radius r does

equal 2πr, but in terms of these coordinates the circumferential speed

of light differs from the radial speed. The former is given by the same

formula as in Einstein’s 1911 paper, but the latter differs from the 1911

formula by a factor of 2 on the “potential” term. To explain this in detail,

we must first consider how the Schwarzschild metric is derived from the field

equations of general relativity.

|

|

|

|

To

deduce the implications of the field equations for observable phenomena

Einstein originally made use of approximate methods, since no exact solutions

were known. These approximate methods were adequate to demonstrate that the

field equations lead in the first approximation to Newton's laws, and in the

second approximation to a natural explanation for the anomalous precession of

Mercury (see Section 6.2). However, these results can now be directly

computed from the exact solution for a spherically symmetric field, found by

Karl Schwarzschild in 1916. As Schwarzschild wrote, it's always pleasant to

find exact solutions, and the simple spherically symmetrical line element

"let's Mr. Einstein's result shine with increased clarity". To this

day, most of the empirically observable predictions of general relativity are

consequences of this simple solution.

|

|

|

|

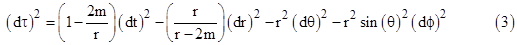

We

will discuss Schwarzschild's original derivation in Section 8.7, but for our

present purposes we will take a slightly different approach. Recall from

Section 5.5 that the most general form of the metrical spacetime line element

for a spherically symmetrical static field (although it is not strictly

necessary to assume the field is static) can be written in polar coordinates

as

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

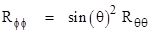

where

gθθ = –r2, gϕϕ = –r2

sin(θ)2, and gtt and grr are functions

of r and the gravitating mass m. (These stipulations ensure that the

circumference of a circular orbit of radius r is 2πr.) We expect that if

m = 0, and/or as r increases to infinity, we will have gtt = 1 and

grr = –1 in order to give the flat Minkowski metric in the absence

of gravity. We saw in Section 5.5 that in this highly symmetrical context

there is a fairly plausible way to derive the metric coefficients gtt

and grr simply from the requirement to satisfy Kepler's third law

and the inverse-square law, but with some ambiguity over the choice between

proper time and coordinate time. We can now determine unambiguously the

values of these metric coefficients consistent with Einstein's field

equations.

|

|

|

|

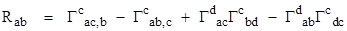

In

any region that is free of (non-gravitational) mass-energy the vacuum field

equations must apply, which means the Ricci tensor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

must

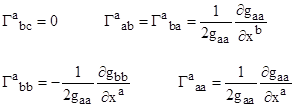

vanish, i.e., all the components are zero. Since our metric is in diagonal

form, it's easy to see that the Christoffel symbols for any three distinct

indices a,b,c reduce to

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

with

no summations implied. In two of the non-vanishing cases the Christoffel

symbols are of the form qa/(2q), where q is a particular metric

component and subscripts denote partial differentiation with respect to xa.

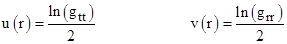

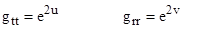

By an elementary identity these can also be written as  . Hence if we define the new variable . Hence if we define the new variable  we can write the Christoffel symbol in

the form Qa with q = e2Q. Accordingly if we define the

variables (functions of r) we can write the Christoffel symbol in

the form Qa with q = e2Q. Accordingly if we define the

variables (functions of r)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

then

we have

|

|

|

|

|

|

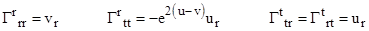

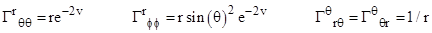

and

the non-vanishing Christoffel symbols (as given in Section 5.5) can be

written as

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

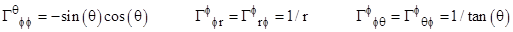

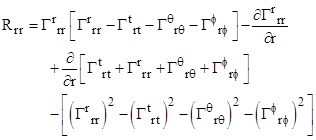

We

can now write down the components of the Ricci tensor, each of which must

vanish in order for the field equations to be satisfied. Writing them out

explicitly and expanding all the implied summations for our line element, we

find that all the non-diagonal components are identically zero (which we

might have expected from symmetry arguments), so the only components of

interest in our case are the diagonal elements

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

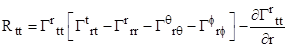

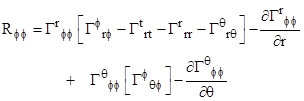

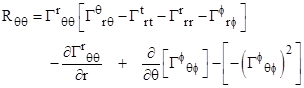

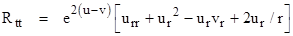

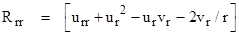

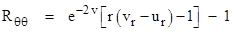

Inserting

the expressions for the Christoffel symbols gives the equations for the four

diagonal components of the Ricci tensor as functions of u and v:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

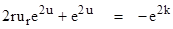

|

The

necessary and sufficient condition for the field equations to be satisfied by

a line element of the form (2) is that these four quantities each vanish.

Combining the expressions for Rtt and Rrr we

immediately have ur = –vr , which implies u = –v + k

for some arbitrary constant k. Making these substitutions into the equation

for Rθθ we get the condition

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

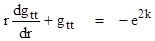

Remembering

that e2u = gtt, and that the derivative of e2u

is 2ur e2u, this condition expresses the requirement

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

left side is just the chain rule for the derivative of the product rgtt,

and since this derivative equals the constant –e2k we immediately

have rgtt = –e2kr + α for some constant α,

and hence gtt = –e2k + α/r. As r increases to

infinity the metric must go over to the Minkowski metric, which has gtt

= 1, so we must have –e2k = 1, which implies that k = πi/2.

Also, since grr = e2v where v = –u + πi/2, it

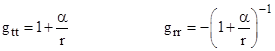

follows that grr = –1/gtt, and so we have the results

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To

match the Newtonian limit we set a

= –2m where m is classically identified with the mass of the gravitating

body. These metric coefficients were derived by combining the expressions for

Rtt and Rrr, but it's easy to verify that they also

satisfy each of those equations separately. Thus, substituting these

expressions into the line element (2), we arrive at the essentially unique

(up to changes in coordinate systems) spherically symmetrical static solution

of Einstein's field equations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

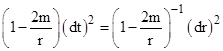

Now

that we have derived the Schwarzschild metric, we can easily correct the

"speed of light" formula that Einstein gave in 1911. A ray of light

always travels along a null trajectory, i.e., with dτ = 0, and for a

radial ray we have dθ and dϕ both equal to zero, so the equation

for the light ray trajectory through spacetime, in Schwarzschild coordinates

(which are essentially the only spherically symmetrical ones in which the

metric is independent of t and the circumference of a circle of radius r is 2πr)

is simply

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

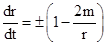

from

which we get

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

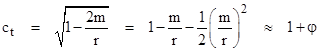

where

the ± sign just

indicates that the light can be going radially inward or outward. (We're

using geometric units, so c = G = 1.) In the Newtonian limit the classical

gravitational potential at a distance r from mass m is φ = –m/r, so if

we let cr = dr/dt denote the radial speed of light in

Schwarzschild coordinates, we have

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

which

corresponds to Einstein's 1911 equation, except that we have a factor of 2

instead of 1 on the potential term. Thus, as φ becomes increasingly

negative (i.e., as the magnitude of the potential increases), the radial

"speed of light" cr defined in terms of the

Schwarzschild parameters t and r is reduced to less than the nominal value of

c. The factor of 2 relative to the equation of 1911 arises because in the

full theory there is gravitational length contraction as well as time

dilation. The length contraction doesn’t affect the gravitational redshift,

which is purely a function of the time dilation, so the redshift prediction

of 1911 remains valid. Only the radial speed of light (in terms of

Schwarzschild coordinates) is changed.

|

|

|

|

On

the other hand, if we define the tangential speed of light at a distance r

from a gravitating mass center in the equatorial plane (θ = π/2) in

terms of the Schwarzschild coordinates as ct = r(dϕ/dt), then

the metric divided by (dt)2 immediately gives

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus,

we again find that the "velocity of light" is reduced a region with

a strong gravitational field, but this speed is the square root of the radial

speed at the same point, and to the first order in m/r this is the same as

Einstein's 1911 formula, although it is understood now to signify just the

tangential speed. This illustrates the fact that the general theory doesn't

lead to a simple scalar field of c values in Euclidean space. The effects of

gravitation can only be accurately represented by a tensor field. (It’s

possible to define so-called isotropic coordinates, as discussed in Section

8.4, in terms of which the speed of light is the same in all directions, but

only by using a radial coordinate in terms of which the circumference of a

circular orbit of radius r is not 2πr, which shows the

non-Euclidean character of the space.)

|

|

|

|

As

mentioned, one of the observable implications of general relativity (as well

as any other metrical theory that respects the equivalence principle) is

gravitational redshift, which is a consequence of the fact that, for any

stationary metric, the rate of proper time at a fixed radial position in a

gravitational field relative to the coordinate time is given by

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

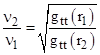

Since

the coordinate time for successive wavecrests to traverse a fixed interval is

the same, the characteristic frequency ν1 of light emitted by

some known physical process at a radial location r1 will represent

a different frequency ν2 with respect to the proper time at

some other radial location r2 according to the formula

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

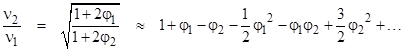

From

the Schwarzschild metric we have gtt(rj) = 1+2φj where φj

= –m/rj is the gravitational potential at rj, so

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

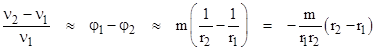

Neglecting

the higher-order terms and rearranging, this can also be written as

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Observations

of the light emitted from the surface of the Sun, and from other stars, is

consistent with this predicted amount of gravitational redshift (up to first

order), although measurements of this slight effect are difficult. A

terrestrial experiment performed by Rebka and Pound in 1960 exploited the

Mossbauer effect to precisely determine the redshift between the top and

bottom of a tower. The results were in good agreement with the above formula,

and subsequent experiments of the same kind have improved the accuracy to

within about 1 percent. (Note that if r1 and r2 are

nearly equal, as, for example, at two heights near the Earth's surface, then

the leading factor of the right-most expression is essentially just the

acceleration of gravity a = –m/r2, and the factor in parentheses

is the difference in heights Δh, so we have Δν/ν = a Δh.)

|

|

|

|

However,

it's worth noting that this amount of gravitational redshift is a feature of

just about any viable metrical theory of gravity that includes the

equivalence principle (e.g., Nordstrom’s scalar theory), so these experimental

results, although useful for validating that principle, are not very robust

for distinguishing between competing theories of gravity. For this we need to

consider other observations, such as the paths of light near a gravitating

body, and the precise orbits of planets. These phenomena are discussed in the

subsequent sections.

|

|

|

|

Return to Table of Contents

|