|

6.3 Bending Light |

|

|

|

When Lil’s husband got demobbed, I said – |

|

I didn’t mince my words, I said to her myself, |

|

HURRY UP PLEASE, IT’S TIME. |

|

T. S. Eliot, 1922 |

|

|

|

At the conclusion of his treatise on Opticks in 1704, the 62 year old Newton lamented that he could "not now think of taking these things into farther consideration", and contented himself with proposing a number of queries "in order to a farther search to be made by others". The very first of these was |

|

|

|

Do not Bodies act upon Light at a distance, and by their action bend its Rays, and is not this action strongest at the least distance? |

|

|

|

From one point of view this may seem like a very natural suggestion. Newton’s theory of universal gravitation already predicted that the path of any material particle (regardless of its composition) moving at a finite speed is affected by the pull of gravity. However, the finite speed of light was not well established in Newton’s time, as discussed in Section 3.3, and it was far from clear that light consists of material particles. These uncertainties precluded Newton from making any definite prediction about whether and how light is affected by gravity. By the late 18th century the finite speed of light was well established so, although the constitution of light was still unknown, it was tempting to apply Newton’s law to compute the deflection of light by gravity – under the assumption that a pulse of light responds to gravitational attraction as does a particle of matter moving at the same speed. If the Sun’s mass is located at the origin of xy coordinates then a particle moving with speed c = 1 along a nearly straight ray y = r0 is subject to acceleration m/r2 where r2 = r02 + x2 is the distance to the Sun. Multiplying this by r0/r gives the component of acceleration a = (m/r2)(r0/r) transverse to the ray. Over any small segment we have y = (1/2)ax2 (since x = t for a ray of light) up to a constant, and hence the angle of the ray is dy/dx = ax = tan(θ) ≈ θ. From this we have dθ/dx = a = mr0/r3, and integrating over the range x = -∞ to +∞ gives, to the lowest order of approximation, the total Newtonian angular deflection, 2m/r0. Of course, this crude derivation applies only to a virtually straight path, and neglects the variation in the speed of the light corpuscle. Around 1784 Cavendish reached the same result by a more rigorous calculation, analyzing the actual hyperbolic path with varying speed, and in 1804 Soldner published the details of such an analysis. |

|

|

|

For this strictly Newtonian analysis, the rectilinear coordinates x,y of a particle are related to the polar coordinates r,θ by x = r cos(θ) and y = r sin(θ). Differentiating with respect to time, we have the components of the velocity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

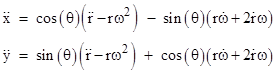

where dots signify time derivatives and we let ω denote dθ/dt. Differentiating again, we get the components of the acceleration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Any vector whose x and y components are proportional to cos(θ) and sin(θ) respectively is parallel to r, and any vector whose x and y components are proportional to –sin(θ) and cos(θ) respectively is perpendicular to r (in the counter-clockwise direction), so it follows from the above expressions that the acceleration vector has the radial and tangential components |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

According to Newton’s theory, a large gravitating body of mass m, located at the origin, exerts a purely radial force of magnitude −m/r2 on a test particle at a distance r from the origin (in geometrical units with G = c = 1), so the Newtonian equations of motion for a test particle are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The right hand equation is equivalent to d(r2ω)/dt = 0, and hence the quantity h = r2ω is a constant. Letting u denote the reciprocal of r, we have r = u-1 and h/ω = u-2, from which it follows that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where we have used the fact that ω = dθ/dt. Substituting for ω and r in the radial equation of motion, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

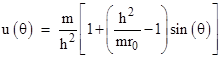

Simplifying, we arrive at the familiar equation for the path of a test particle in a stationary spherical gravitational field according to Newtonian theory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The general solution of this equation can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

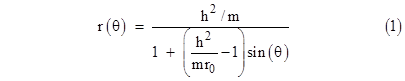

If the speed of the particle were infinite, then h would be infinite, and the equation of motion would reduce to r(θ) = 1/Asin(θ), which is simply the equation of a straight line as θ ranges from 0 to π, so there would be no gravitational deflection. However, given the finite speed of the hypothesized particle of light, and hence a finite value of h, we can solve this equation to determine the predicted gravitational deflection based on the Newtonian assumptions. Letting r0 denote the distance of the pulse of light at its closest approach to the gravitating body (θ = π/2), at which point du/dθ = 0, the constant of integration can be written as A = 1/r0 – m/h2. Inserting this into the above equation, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

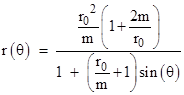

Reverting back to the radial coordinate r, we get the general equation for the path of a test particle in a spherical stationary gravitational field according to Newtonian theory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

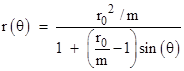

This is the equation of a conic section, which is an ellipse, a hyperbola, or a parabola, accordingly as the eccentricity parameter (the coefficient of sin(θ)) is less than, greater than, or equal to 1. Now, assuming a light pulse has the speed 1 at the perigee (recalling that we’ve chosen units so c=1), we have ωr0 = 1 at this condition, and hence h = r0. Therefore we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

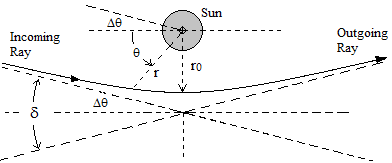

The eccentricity is extremely large (since r0 is much greater than m), so the path is a hyperbola that differs only slightly from a straight line, as indicated in the figure below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

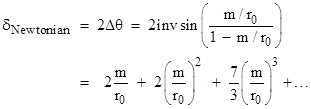

The asymptotes of this hyperbola occur at the angles where r goes to infinity, so we need only determine the angles q such that the denominator of the expression for r vanishes. Thus the asymptotic angles satisfy sin(θ) = (−m/r0)/(1 − m/r0), which gives to the first order the half deflection angle Δθ ≈ m/r0, so the total deflection is δ ≈ 2m/r0. More precisely we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Incidentally, we assumed (with Soldner) that the speed of the light corpuscle (treated as a material particle) is c at the perigee, which according to Newtonian mechanics implies that the speed must be slightly less than c when the corpuscle is far from the Sun, since it’s speed increases due to the Sun’s pull as it approaches. As an alternative, we might postulate (with Cavendish) that the speed is c at infinity, in which case Newtonian mechanics implies that the speed v0 at perigee must be slightly greater than c. The change in potential energy of a particle of unit mass from infinity to the perigee is m/r0, which must equal the change in kinetic energy given by v02/2 – c2/2. Again in units with G = c = 1 this gives v02 = 1 + 2m/r0, from which we get h2 = r02 + 2mr0. Substituting this into equation (1), we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus the asymptotic half-angle satisfies sin(θ) = (−m/r0)/(1 + m/r0), which again leads to the first-order result 2m/r0 for the total deflection. (The even-order terms in the exact series are negated.) Hence, regardless of whether we assume the speed of light is c at the perigee or at infinity, this is the amount of (first order) deflection predicted by Newton’s theory of gravity on the assumption that a pulse of light has the same trajectory as a material particle. |

|

|

|

The best natural opportunity to observe this deflection would be to look at the stars near the perimeter of the Sun during a solar eclipse. The mass of the Sun in gravitational units is about m = 1475 meters, and a beam of light just skimming past the Sun would have a closest distance equal to the Sun's radius, r = (6.95)108 meters. Therefore, the Newtonian prediction would be 0.000004245 radians, which equals 0.875 seconds of arc. (There are 2π radians per 360 degrees, each of degree representing 60 minutes of arc, and each minute represents 60 seconds of arc.) |

|

|

|

However, there is a problematical aspect to this "Newtonian" prediction, because it's based on the assumption that particles of light can be accelerated and decelerated just like ordinary matter, and yet if this were the case, it would be difficult to explain why (in non-relativistic absolute space and time) all the light that we observe is traveling at a single characteristic speed. Admittedly if we posit that the rest mass of a particle of light is extremely small, it might be impossible to interact with such a particle without imparting to it a very high velocity, but this doesn't explain why all light seems to have precisely the same speed, as if this particular speed is somehow a characteristic property of light. As a result of these considerations, especially as the wave conception of light began to supersede the corpuscular theory, the idea that gravity might bend light rays was largely discounted in Newtonian physics. (The same fate befell the idea of black holes, originally proposed by Michell based on the Newtonian escape velocity for light. Laplace also mentioned the idea in his Celestial Mechanics, but deleted it in the third edition, possibly because of the conceptual difficulties discussed here.) |

|

|

|

The idea of bending light was revived in Einstein's 1911 paper "On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light". Oddly enough, the quantitative prediction given in this paper for the amount of deflection of light passing near a large mass was identical to the old Newtonian prediction, δ = 2m/r0. In contrast, a competing relativistic theory of gravity, put forward by Nordstrom at around the same time, predicted no light deflection at all. |

|

|

|

There were several attempts to measure the deflection of starlight passing close by the Sun during solar eclipses to test Einstein's prediction in the years between 1911 and 1915, but all these attempts were thwarted by cloudy skies, logistical problems, the First World War, etc. Einstein became very exasperated over the repeated failures of the experimentalists to gather any useful data, because he was eager to see his prediction corroborated, which he was certain it would be. He wrote to Besso in March 1914 |

|

|

|

Now I am fully satisfied, and I do not doubt any more the correctness of the whole system, whether the observations of the eclipse succeed or not. The sense of the thing is too evident. |

|

|

|

Ironically, if any of those early experimental efforts had succeeded in collecting useful data, they would have proven Einstein wrong. It wasn't until late in 1915, as he completed the general theory, that Einstein realized his earlier prediction was incorrect, and the angular deflection should actually be twice the size he predicted in 1911. (See Section 8.9.) Had the World War not intervened, it's likely that Einstein would never have been able to claim the bending of light (at twice the “Newtonian” value) as a prediction of general relativity. At best he would have been forced to explain, after the fact, why the observed deflection was actually consistent with the completed general theory. Luckily for Einstein, he corrected the light-bending prediction before any expeditions succeeded in making useful observations. In 1919, after the war had ended, scientific expeditions were sent to Sobral in South America and Principe in West Africa to make observations of the solar eclipse. (Was the specific location of Principe chosen for its name, as a subliminal tribute to Newton’s Principia?) The reported results were angular deflections of 1.98 ± 0.16 and 1.61 ± 0.40 seconds of arc, respectively, which was taken as clear confirmation of general relativity's prediction of 1.75 seconds of arc. This success, combined with the esoteric appeal of bending light and the romantic adventure of the eclipse expeditions themselves contributed enormously to making Einstein a world celebrity. (One of the original photographic plates from this expedition appears on the cover of this book.) |

|

|

|

One other intriguing aspect of the story, in retrospect, is the fact that there is some doubt about whether the measurement techniques used by the 1919 expeditions were precise enough to have legitimately detected the deflections which were reported, and whether the reported results might have been influenced by what Eddington wanted and expected to see. It’s interesting to speculate on what values would have been recorded if astronomers had managed to take readings in 1914, when the expected deflection was still just 0.875 seconds of arc. (It should be mentioned that subsequent observations, summarized below, have independently confirmed the angular deflection predicted by general relativity, i.e., twice the "Newtonian" value.) |

|

|

|

For historical interest, the approximation methods used by Einstein in 1911 and 1915 to derive the relativistic prediction for the bending of light past the Sun are described in Section 8.9, but here we will base our analysis on the exact Schwarzschild solution. At the outset we should note that the speed of light is not generally isotropic in terms of Schwarzschild coordinates, so angles differ from those measured in isotropic coordinates (such as local inertial coordinates), but the Schwarzschild coordinates can be used to compute the central angle between the asymptotic rays to infinite distance, which is essentially the deflection angle for light rays grazing the Sun as seen on the Earth. |

|

|

|

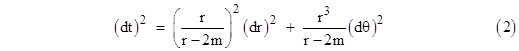

We could make use of the results of Section 6.2 by adapting equation (11) of that section to account for the fact that dτ = 0 for a light path, and then integrate to give the deflection. Another approach would be to evaluate the solution of the basic geodesic equations with arbitrary path parameter (instead of the proper time), adapted to null paths, but this would require us to deal with a three-dimensional manifold. For null paths with a stationary metric it’s more efficient to consider the problem from a two-dimensional standpoint. Recall the Schwarzschild metric in the usual polar coordinates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

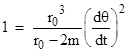

We'll restrict our attention to a single plane through the center of mass by setting ϕ = 0, and since light travels along null paths, we set dτ = 0, which allows us to write the remaining terms in the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

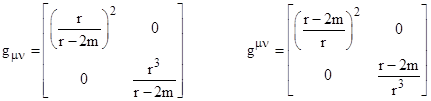

This can be regarded as the (positive-definite) line element of a two-dimensional surface (r, θ), with the parameter t serving as the metrical distance. The null paths satisfying the complete spacetime metric with dτ = 0 are stationary if and only if they are stationary with respect to (2). This implies Fermat’s Principle of “least time”, i.e., light follows paths that minimize the integrated time of flight, or, more generally, paths for which the elapsed Schwarzschild coordinate time is stationary, as discussed in Section 3.4. (Equivalently, we have an angular analog of Fermat’s Principle, i.e., light follows paths that make the integral of the angular displacement dθ stationary, because the coefficients of (2) are independent of both t and q.) Therefore, we need only determine the geodesic paths on this surface. The covariant and contravariant metric tensors are simply |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

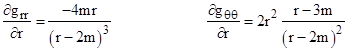

and the only non-zero partial derivatives of the components of gmn are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

so the non-zero Christoffel symbols (of the second kind, as defined in Section 5.4) are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taking the coordinate time t as the path parameter (since it plays the role of the metrical distance in this geometry), the two equations for geodesic paths on the (r, q) surface are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

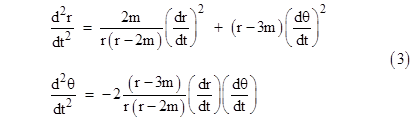

These equations of motion describe the paths of light rays in a spherically symmetrical gravitational field in terms of Schwarzschild coordinates. The figure below shows the paths of a set of parallel incoming rays. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The dotted circles indicate radii of m, 2m, ..., 6m from the mass center. Needless to say, a typical star's physical radius is much greater than it's gravitational radius m, so we will not find such severe deflection of light rays, even for rays grazing the surface of the star. However, for a "black hole" we can theoretically have rays of light passing at values of r on the same order of magnitude as m, resulting in the paths shown in this figure. Interestingly, a significant fraction of the oblique incoming rays are "scattered" back out, with a loop at r = 3m, which is the "light radius". As a consequence, if we shine a broad light on a black hole, we would expect to see a "halo" of back-scattered light outlining a circle with a radius of 3m. |

|

|

|

To quantitatively assess the angular deflection of a ray of light passing near a large gravitating body, note that in terms of the variable u = dθ/dt the second geodesic equation (3) has the form (1/u)du = −[(2/r)(r−3m)/(r−2m)]dr, which can be integrated immediately to give ln(u) = ln(r−2m) − 3ln(r) + C, so we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To determine the value of K, we divide the metric equation (2) by (dt)2 and evaluate it at the perihelion r = r0, where dr/dt = 0. This gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

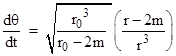

Substituting into the previous equation we find K2 = r03/(r0 - 2m), so we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

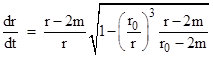

Now we can substitute this into the metric equation divided by (dt)2 and solve for dr/dt to give |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

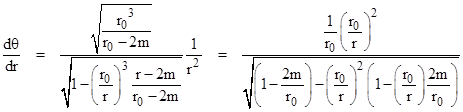

Dividing dθ/dt by dr/dt then gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

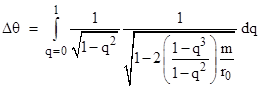

Integrating this from r = r0 to ∞ gives the mass-centered angle ∆θ swept out by a photon as it moves from the perihelion out to an infinite distance. In terms of the parameter q = r0/r, noting that dr = –(r0/q2)dq, this leads to the equation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

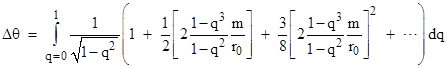

The magnitude of the second term in the right-hand square root is always less than 1 provided r0 is greater than 3m (which is the radius of light-like circular orbits, as discussed further in Section 6.5), so we can expand the square root into a power series in that quantity. The result is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

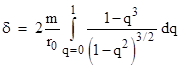

This can be analytically integrated term by term. The integral of the first term is just p/2, as we would expect, since with a mass of m = 0 the photon would travel in a straight line, sweeping out a right angle as it moves from the perihelion to infinity. The remaining terms supply the “excess angle”, which represents the central angle between the perihelion and the out-going asymptote. If m/r0 is small, only the first-order term is significant. Since the path of light is symmetrical about the perihelion, the total angular deflection between the in-coming and out-going asymptotes is twice the excess of the above integral beyond π/2. Focusing on just the first order term, the total asymptotic deflection of the light ray is therefore |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

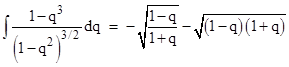

Evaluating the integral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

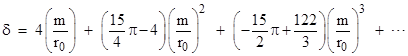

from q = 0 to 1 gives the constant factor 2, so the first-order deflection is δ = 4m/r0. This gives the relativistic value of 1.75 seconds of arc, which is twice the “Newtonian” value. To higher orders in m/r0 we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The difficulty of performing precise measurements of optical starlight deflection during an eclipse can be gathered from the following list of results: |

|

|

|

Optical Deflection of Starlight During Eclipses |

|

|

|

Date Location arc secs |

|

|

|

29 May 1919 Sobral 1.98 ± 0.16 |

|

Principe 1.61 ± 0.40 |

|

21 Sep 1922 Australia 1.77 ± 0.40 |

|

1.42 to 2.16 |

|

1.72 + 0.15 |

|

1.82 ± 0.20 |

|

9 May 1929 Sumatra 2.24 ± 0.10 |

|

19 Jun 1936 USSR 2.73 ± 0.31 |

|

Japan 1.28 to 2.13 |

|

20 May 1947 Brazil 2.01 ± 0.27 |

|

25 Feb 1952 Sudan 1.70 ± 0.10 |

|

30 Jun 1973 Mauritania 1.66 ± 0.19 |

|

|

|

Fortunately, much more accurate measurements can now be made in the radio wavelengths, especially of quasars, since such measurements can be made from observatories with the best equipment and careful preparation (rather than hurriedly in a remote location during a total eclipse). In particular, the use of Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), combining signals from widely separate observatories, gives a tremendous improvement in resolving power. With these techniques it’s now possible to precisely measure the deflection (due to the Sun’s gravitational field) of electromagnetic waves from stars at great angular distances from the Sun. According to Will, an analysis in 2004 of over 2 million VLBI observations has shown that the ratio of the actual observed deflections to the deflections predicted by general relativity is 0.99992 ± 0.00023. Thus the dramatic announcement of 1919 has been retro-actively justified. |

|

|

|

The results of Eddington’s expedition reached Einstein by way of a telegram from Lorentz on September 22. (“Eddington found stellar shift at solar limb, tentative value between nine-tenths of a second and twice that.”). On the 7th of October Lorentz followed with a letter, providing details of Eddington’s presentation to the “British Association at Bournemouth”. Oddly enough, at this meeting Eddington reported that “one can say with certainty that the effect (at the solar limb) lies between 0.87″ and 1.74″, although he qualified this by saying the plates had been measured only preliminarily, and the final value was still to be determined. In any case, Lorentz’s letter also included a rough analysis of the amount of deflection that would be expected due to ordinary refraction in the gas surrounding the Sun. His calculations indicated that a suitably chosen gas density at the Sun’s surface could indeed produce a deflection on the order of 1″, but for any realistic density profile the effect would drop off very rapidly for rays passing just slightly further from the Sun. Thus the effect of refraction, if there was any, would be easily distinguishable from the relativistic effect. He concluded |

|

|

|

We may surely believe (in view of the magnitude of the detected deflection) that, in reality, refraction is not involved at all, and your effect alone has been observed. This is certainly one of the finest results that science has ever accomplished, and we may be very pleased about it. |

|

|