|

8.5 Scholium |

|

|

|

I earnestly ask that all this be appraised honestly, and that deficiencies in matters so very difficult be not so much reprehended as investigated and kindly supplemented by new endeavors of my readers. |

|

Isaac Newton, 1687 |

|

|

|

Considering that the first Scholium of Newton's Principia begins with the famous assertion "absolute, true, and mathematical time...flows equably, without relation to anything external", it's ironic that Newton's theory of universal gravitation can be very closely represented as a theory of variations in the flow of time. Suppose in Newton's absolute space we establish Cartesian coordinates x,y,z, and then assign a fourth coordinate, t, to every point. We call this the time parameter, but we allow for the possibility that the effective elapsed time along an incremental timelike path (i.e., a sequence of consecutive events for a given material particle) is dτ, given by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

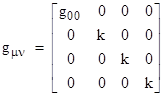

The Galilean assumption was that a single set of assignments of the time coordinate t to events corresponds to the lapses of proper time dτ along any and all paths, which implies that g00 = 1 and k = 0. However, this can only be known to within some observational tolerance. Strictly speaking we can say only that g00 is extremely close to 1, and the constant k is very close to zero (in conventional units of measure). |

|

|

|

Using indices with x0 = t, x1 = x, x2 = y, and x3 = z, we can re-write (1) with the usual summation convention as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

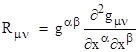

Now, we could compute the Riemann curvature tensor, and contract it to give the Ricci tensor, which would then enable us to write a generally covariant field equation, but for our purposes it suffices to define an array (analogous to the Ricci tensor) composed of the second partial derivatives of the metric components |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

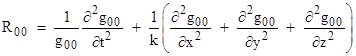

The only non-zero component of this array for our hypothesized metric is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

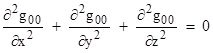

If we assume g00 is independent of the coordinate t (meaning that the metrical configuration is static), the first term vanishes and we find that R00 is just the scaled Laplacian of g00. Hence if we take our vacuum field equations to be Rμν = 0 (analogous to the vanishing of the Ricci tensor in general relativity) this is equivalent to requiring that the Laplacian of g00 vanish, i.e., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

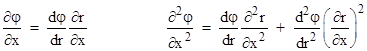

For convenience let us define the scalar φ = g00/2. If we consider just spherically symmetrical fields about the origin, we have φ = φ(r) and so |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and

similarly for the partials with respect to y and z. Since |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and similarly for the y and z partials. Making these substitutions back into the Laplace equation gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This simple linear differential equation has the unique solution dφ/dr = J/r2 where J is a constant of integration, and so we have φ = −J/r + K for some constants J and K. |

|

|

|

Incidentally, this above discussion applies only in three space dimensions. If we were working in just two dimensions, the constant "2" in the above equation would be "1", and the unique solution would be dφ/dr = J/r, giving φ = J ln(r) + K. This shows that our neo-Newtonian gravity "works" only with three space dimensions, just as general relativity works only with four space-time dimensions. |

|

|

|

Now that we've solved for the g00 field we need the equations of motion. We assume that objects in gravitational free-fall follow geodesics through the spacetime, so the equations of motion are just the geodesic equations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where xα denote the quasi-Euclidean coordinates t,x,y,z defined above. Since we have assumed that the scale factor k between spatial and temporal coordinates is virtually zero, and that g00 is nearly equal to unity, it's clear that all the speed components dx/dτ, dy/dτ, dz/dτ are extremely small, whereas the derivative dt/dτ is virtually equal to 1. Neglecting all terms containing one or more of the speed components, we're left with the zeroth-order approximation for the spatial accelerations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From the definition of the Christoffel symbols we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and similarly for the Christoffel symbols in the y and z equations. Since the metric components are independent of time, the partials with respect to t are all zero. Also, the metric tensor gμν and its inverse gμν are both diagonal and the non-zero components of the latter are virtually equal to 1, 1/k, 1/k, 1/k. All the mixed components of gμν vanish, so we are left with |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and similarly for Γytt and Γztt. As a result, the equations of motion in the weak slow limit are closely approximated by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We've seen that the Laplace equation requires gtt to be of the form 2K − 2J/r for some constants K and J in a spherically symmetrical field, and since we expect dt/dτ to approach 1 as r increases, we can set 2K = 1. With gtt = 1 − 2J/r we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and similarly for the partials with respect to y and z. Therefore the approximate equations of motion in the weak slow limit are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If we set J/k = −m, i.e., to the negative of the mass of the gravitating source, these are exactly the equations of motion for Newton's inverse-square attraction. Interestingly, this implies that precisely one of J,k is negative. If we choose to make J negative, then the gravitational "potential" has the form gtt = 1 + 2|J|/r, which signifies that the potential would increase as we approach the source, as would the rate of proper time along a stationary worldline with respect to coordinate time. In such a universe the value of k would need to be positive in order for gravity to be attractive, i.e., in order for geodesics to converge on the gravitating source. On the other hand, if we choose to make J positive, so that the potential and the rate of proper time decrease as we approach the source, then the constant k must be negative. Referring back to the original line element, this implies an indefinite metric. Naturally we can scale our units so that |k| = 1, but the sign of k is significant. Thus from the observation that "things fall down", we can nearly infer the Minkowski metrical structure of spacetime. If we combine this observation with the empirical fact that light emerging from a gravitational field is redshifted (which is a necessary consequence of the equivalence principle), the Minkowski metric follows uniquely. Thus, even without pre-supposing special relativity, we find that locally Minkowskian spacetime is the only basis on which a viable metrical theory of gravity can be constructed. In this sense, special relativity emerges unavoidably from the simple facts of Newtonian gravity viewed in a space-time framework. |

|

|

|

The fact that we can derive the correct trajectories of free-falling objects based on either of two diametrically opposed assumptions is not without precedent. This is very closely related to how Descartes and Newton were able to deduce the correct law of refraction based on the assumption that light travels more rapidly in denser media, while Fermat deduced the same law from the opposite assumption. |

|

|

|

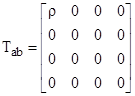

In any case, taking k = −1 and J = m, we see that Newton's law of gravitation in the vacuum is Rμν = 0, closely paralleling the vacuum field equations of general relativity, which represents the vanishing of the Laplacian of g00/2. At a point with non-zero mass density we simply set this equal to 4πρ to give Poisson's equation. Hence if we define the energy-momentum array |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

we can express Newton's geometrical spacetime law of gravitation as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This can be compared with Einstein's field equations (equation (3) of Section 5.8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Of course the "R" and "T" arrays in Newton's law are based on simple partial derivatives, rather than covariant differentiation, so they are not precisely identical to the Ricci tensor and the energy-momentum tensor of general relativity. However, the definitions are close enough that the tensors of general relativity can rightly be viewed as the natural generalizations of the simple Newtonian arrays. The above equations show that the acceleration of gravity is proportional to the rate of change of gtt as a function of r. At any given r we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

so gtt corresponds to the squared "rate of proper time" (with respect to coordinate time) at the given r. It follows that our feet are younger than our heads, because time advances more slowly as we get closer to the center of the field. So, despite Newton's conception of the perfectly equable flow of time, his theory of gravitation can well be interpreted as a description of the effects of the inequable flow of time. In essence, the effect of Newtonian gravity can be explained in terms of the flow of time being slower near massive objects, and just as a refracted ray of light veers toward the medium in which light goes more slowly (and as a tank veers in the direction of the slower tread-track), objects progressing in time veer in the direction of slower proper time, causing them to accelerate toward massive objects. |

|

|